Solipsism, subjectivity, and the limits of solitary metaphysics

Prologue

The Suspicion That Everything Might Be Mine

There is a moment, usually quiet and almost imperceptible, in which the world feels strangely interior.

(more…)Solipsism, subjectivity, and the limits of solitary metaphysics

Prologue

The Suspicion That Everything Might Be Mine

There is a moment, usually quiet and almost imperceptible, in which the world feels strangely interior.

(more…)Freedom, Possession, and the Fracture of Intimacy in Nicolas Roeg

This essay approaches Bad Timing (1980) not as a scandal to be adjudicated nor as a relic to be defended, but as a structure to be entered. Its method is hybrid: discursive rather than footnoted, analytic without academic apparatus, attentive to psychology, philosophy, criminology, aesthetics, and reception history without subordinating the film to any single interpretive regime. What follows is not a verdict but an excavation.

The twenty sections unfold deliberately. The opening movements situate the film within its material and cultural conditions—production history, institutional repudiation, early critical recoil. From there, the essay turns inward to the film’s fractured narrative architecture, examining how non-linear chronology reshapes moral perception. The central constellation of characters—Milena, Alex, Stefan, and Inspector Netusil—emerges next, each approached first descriptively, then through competing interpretive lenses.

Subsequent sections stage a series of tensions: Milena as pathological versus Milena as Dionysian; Alex as narcissistic offender versus Alex as Romantic sufferer; the relationship viewed through existential philosophy versus criminological accountability. These frameworks are not reconciled but allowed to remain in productive conflict. Only after this layering does the essay articulate affirmative and negative moral currents embedded within the film’s design.

The closing movements trace the film’s investigative intelligence, its initial rejection, its institutional rehabilitation—most notably through The Criterion Collection—and its contemporary standing as one of Nicolas Roeg’s defining works.

Throughout, the guiding premise is simple: “Bad Timing” is a film about possession, freedom, and the instability of narrative control. To read it adequately requires resisting simplification. This essay invites that resistance.

(more…)From Canonical Readings to Speculative Excess

Few films in the history of cinema have generated as sustained, diverse, and often contradictory a body of interpretation as Persona. Since its release in 1966, Ingmar Bergman’s work has occupied a singular position within the canon of modernist film: at once intimate and abstract, austere and volatile, narratively minimal yet interpretively inexhaustible. To write about Persona is therefore to enter a preexisting field of discourse already dense with analysis.

This essay does not seek to resolve that density. Instead, it proceeds from the assumption that the film’s power resides precisely in its capacity to sustain multiple intensities of reading. Psychological, feminist, existential, theological, political, and meta-cinematic frameworks have all found persuasive grounding within its structure. At the same time, the film has inspired playful exaggerations and reductive simplifications, each revealing something about the viewer’s desire for coherence.

The structure of the present study follows a progression through these interpretive layers. We begin with production context and narrative architecture, then move through Bergman’s own statements and silences, canonical critical frameworks, speculative expansions, reductive readings, psychoanalytic rupture, modernist self-reflexivity, and reception history. Only in the epilogue do we venture a provisional synthesis aligned with an impressionistic understanding of the film’s aesthetic method.

The guiding premise is simple: Persona is not exhausted by any single explanatory model. Its fragmentation is not an obstacle to interpretation but the condition of its vitality. To approach it in film scholar mode is therefore not to impose closure, but to map the contours of its resistance to closure.

What follows is not a solution, but a cartography.

Released in 1966, Persona occupies a decisive position within the career of Ingmar Bergman and within postwar European art cinema more broadly. Initially conceived under the working title Kinematografi, the film was reportedly written while Bergman was hospitalized with pneumonia, during what he later described as a profound personal and artistic crisis. He would retrospectively claim that the film “saved” his life, marking both a culmination and a rupture in his creative trajectory. Though originally commissioned for Swedish television, the work ultimately premiered theatrically, where it received mixed critical responses: some reviewers dismissed it as excessively experimental, while others immediately recognized its formal audacity and philosophical ambition.

The film also marks the first collaboration between Liv Ullmann and Bergman, inaugurating a partnership that would become central to his late career. Ullmann appears alongside Bibi Andersson, whose collaboration with Bergman predated this production. The cinematography by Sven Nykvist is widely regarded as revolutionary, particularly in its use of high-contrast black-and-white imagery and extreme close-ups. Portions of the film were shot on the island of Fårö, a location that would become Bergman’s home and recur in subsequent works. The visual austerity of the coastal landscape contributes significantly to the film’s atmosphere of isolation and psychological exposure.

The narrative structure is framed by an overtly self-reflexive prologue. The film opens with a projector flickering to life, fragments of celluloid passing through the gate, and a montage of discontinuous images: a silent comedy clip, a spider, a nail driven into a hand, a sheep being slaughtered, an erect penis, and a young boy reaching toward an indistinct female face on a screen. At one point the film strip appears to burn, exposing the material substrate of cinema itself. These gestures foreground the constructed nature of the medium before the primary narrative has commenced.

The plot centers on Elisabet Vogler, a celebrated stage actress who abruptly ceases speaking during a performance of Electra. Medical examinations reveal no organic cause; her silence appears voluntary. A psychiatrist, Dr. Steen, assigns nurse Alma to care for her and arranges for the two women to reside temporarily at her seaside cottage. In this isolated environment, Alma begins speaking extensively about her personal life, including her fiancé, her ambitions, and a formative sexual encounter that resulted in an abortion. This monologue was filmed twice, once emphasizing Alma’s narration and once emphasizing Elisabet’s silent reception, and later intercut in the final edit.

Alma eventually discovers an unsealed letter written by Elisabet to the doctor, in which she describes and evaluates Alma’s confessions in detached terms. The discovery precipitates a rupture in their relationship. Tension escalates: Alma confronts Elisabet; broken glass is left on a path, cutting Elisabet’s foot; affection alternates with resentment. A pivotal scene recounting Elisabet’s apparent rejection of her son is presented twice, each version focusing on a different face, one of them in a single take lasting over six minutes. Later, the two women stand before a mirror, and their faces appear to merge into a composite image, one of the most iconic shots in modern cinema.

The film concludes with Alma packing to leave the cottage. The apparatus of filmmaking becomes visible once more, camera and crew exposed, returning the viewer to the self-conscious materiality announced in the prologue.

Any sustained scholarly engagement with Persona must account not only for the film itself but also for Ingmar Bergman’s extensive, though carefully delimited, commentary on it. Bergman repeatedly described the work as his most important film, asserting that it had “saved” him during a period of illness and existential crisis. Written while he was hospitalized with pneumonia, the screenplay emerged, by his own account, from a state of psychological extremity. He characterized the film as the product of a violent personal reaction, one that threatened him physically and mentally. The creative act, in this framing, becomes both therapeutic and salvific.

Bergman also articulated a structural understanding of the film. He referred to it as a “sonata for two instruments,” emphasizing counterpoint: nurse and patient, love and absence of love, reality and dream. The film’s organization, he suggested, was deliberately musical rather than narrative in a conventional sense. This formal self-awareness extends to his explanation of the burning film strip in the prologue. The rupture of the celluloid was intended as a reminder to the audience that what they were watching was manufactured. Cinema, here, is not illusion sustained but illusion exposed.

Thematically, Bergman linked Elisabet’s silence to his own periods of withdrawal, moments when speech became impossible. He spoke of the insufficiency of art and of language, suggesting that the actress’s refusal to speak arose from a recognition of the emptiness of her performed words. In this context, Persona becomes a meditation on authenticity and the hopeless dream of being rather than merely seeming. Notably, Bergman also declared that during the making of the film he ceased caring whether the result would appeal to audiences, marking a decisive shift in his relation to reception.

Yet these statements coexist with a striking refusal to authorize interpretation. Bergman never claimed that Persona possessed a single definitive meaning. He did not confirm that the relationship between Alma and Elisabet was explicitly lesbian or romantic. He did not identify the boy in the prologue as autobiographical, despite frequent speculation. He offered no explanation for the inclusion of the spider, the nail, the slaughtered sheep, or the brief news footage of self-immolation that some critics have read as political commentary linked to Cold War anxieties.

Similarly, Bergman never clarified whether the merging of faces should be understood literally within the diegesis or metaphorically as a visual abstraction. He did not connect the title explicitly to Jungian psychology, despite its resonance with the concept of the persona as social mask. Nor did he designate the film as a feminist statement, even though it centers exclusively on female subjectivity. He refrained from specifying whether Elisabet’s silence was protest, weakness, strength, or pathology. Finally, although he once suggested that he had gone as far as he could go with this film, he did not declare it a summation of his career and continued directing for decades thereafter.

The result is a paradoxical authorial posture: abundant reflection combined with interpretive restraint. Bergman provides context, structure, and affective origins, yet systematically declines to foreclose the film’s semantic plurality.

Over the decades, Persona has generated an extraordinary range of serious interpretative frameworks, many of which have attained canonical status within film studies. Among the most persistent is the reading of psychological doubling. In this view, Alma and Elisabet are not merely two characters but two aspects of a divided psyche. Alma embodies expression, emotional immediacy, and confessional excess; Elisabet represents withdrawal, silence, and repression. The merging of their faces, achieved through precise cinematographic superimposition, becomes the visual correlative of psychic fragmentation and recomposition.

Closely aligned with this is the broader thesis of identity crisis. The film stages the instability of selfhood under conditions of extreme relational intensity. Identities dissolve, overlap, and recombine. The nurse begins to echo the actress; the actress absorbs the nurse’s disclosures. The husband’s mistaken identification of Alma as Elisabet dramatizes this permeability. Subjectivity appears contingent, dependent upon the gaze and speech of the other.

A feminist interpretation situates the film within the pressures placed upon women’s roles, particularly the tension between motherhood and individual autonomy. Elisabet’s apparent rejection of her son functions as a focal point for debates about maternal expectation and guilt. The repeated monologue addressing this rejection foregrounds shame as structuring affect, shaping both identity and interpersonal dynamics. In related fashion, queer and bisexual readings emphasize the intense intimacy between the women, interpreting their proximity and emotional entanglement as an exploration of fluid sexual identity.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, the film invites Freudian and Lacanian analysis. Alma’s extended confession of a beach encounter culminating in abortion exposes repressed desire and ambivalence. The oscillation between idealization and hostility within the dyad mirrors analytic transference. The vampiric interpretation, also present in serious criticism, casts Elisabet as parasitic, feeding upon Alma’s disclosures to reconstruct her own damaged identity.

Existentialist readings foreground the void at the center of the narrative. Elisabet’s silence becomes a response to the perceived emptiness of language and the performative falseness of social roles. In this light, the film registers a theological crisis as well: silence may stand in for the absence of God, a continuation of Bergman’s earlier explorations of divine muteness.

Other critics emphasize meta-cinematic dimensions. The visible film equipment, the burning celluloid, and the fragmentation of narrative align the work with modernist principles. The film comments upon its own status as representation, interrogating the artificiality of performance and the insufficiency of art in the face of suffering. Political readings have also emerged, linking the brief news footage of self-immolation to Cold War anxieties and global crisis.

Taken together, these interpretations do not cancel one another but form a dense constellation. Each isolates a structural or thematic axis within the film’s architecture, demonstrating its capacity to sustain multiple rigorous frameworks simultaneously.

If the previous section surveyed established critical frameworks, it is equally instructive to observe the proliferation of deliberately outlandish interpretations that Persona has inspired. These readings, while often playful, illuminate the film’s remarkable elasticity and its resistance to interpretive closure.

One speculative theory posits Elisabet as an extraterrestrial observer, her silence functioning as a methodological constraint designed to prevent contamination of her study of human behavior. Within this framework, Alma becomes an unwitting experimental subject, her confessions data extracted by an alien intelligence. Another temporal hypothesis suggests that Alma and Elisabet are the same woman at different points in her life, trapped within a paradoxical loop in which the younger self confronts her future incarnation.

Supernatural and literary analogies have also emerged. The film has been read as a reverse Dorian Gray, in which Elisabet preserves her public beauty by transferring emotional burdens to Alma, who functions as a living portrait. Alternatively, the cottage has been imagined as a containment space for a hybrid vampire-werewolf dyad, their psychological merging reinterpreted as the suppression of monstrous identities. The vampiric dimension reappears here in exaggerated form, no longer metaphorical but literal.

Other interpretations adopt meta-cultural or conspiratorial tones. The burning film and self-reflexive gestures have prompted suggestions that the work itself behaves like a sentient virus, infecting viewers’ consciousness. A tongue-in-cheek reading frames the film as covert tourism propaganda for the island of Fårö, its stark landscapes subliminally encouraging visitation. Corporate allegories recast the merging of identities as a metaphor for the consolidation of Swedish film studios. In similarly satirical fashion, the fragmented narrative has been likened to the frustration of assembling IKEA furniture without clear instructions, Elisabet’s silence symbolizing the absent manual.

Temporal-cultural extrapolations extend further. The duality of the women has been interpreted as a prophetic prefiguration of ABBA’s formation, the merging of pairs into a singular cultural entity. A political parody construes the film as an oblique explanation of Sweden’s complex tax code in the 1960s, Elisabet’s refusal to speak representing strategic avoidance. In another imaginative extension, the isolated setting becomes the site of a secret government weather-control experiment, with emotional states linked to atmospheric manipulation.

While these readings strain plausibility, they underscore a crucial feature of Persona: its structural openness invites projection. The film’s sparse exposition, charged imagery, and discontinuities create a semantic vacuum capable of accommodating wildly divergent hypotheses. The more extravagant the interpretation, the more evident the work’s capacity to absorb and refract imaginative excess without collapsing into incoherence.

If outlandish interpretations expand Persona into speculative excess, simplistic readings move in the opposite direction, seeking to reduce its ambiguities to singular explanatory mechanisms. These approaches are often motivated by a desire to restore narrative coherence to a work that persistently disrupts it.

One of the most common reductive frameworks proposes that the entire film is merely a dream, perhaps Alma’s. In this reading, the discontinuous prologue, the merging faces, and the self-reflexive ruptures become dream imagery, thereby neutralizing their ontological threat. Closely related is the literal identification thesis: Alma and Elisabet are simply the same person suffering from what is now termed dissociative identity disorder. The apparent doubling is not metaphorical but diagnostic.

Other interpretations attribute Elisabet’s silence to pragmatic motives. She may be feigning muteness to escape professional obligations or to secure respite from public scrutiny. The crisis thus becomes an instance of celebrity burnout rather than existential collapse. Alternatively, Elisabet is conducting a deliberate social experiment, testing how others respond to silence. In such accounts, her behavior is strategic rather than symptomatic.

Interpersonal motivations are also simplified. The narrative is recast as a conventional love triangle involving jealousy over Elisabet’s husband. Alma’s emotional turbulence becomes romantic rivalry rather than identity crisis. The letter scene is interpreted narrowly as gossip-induced resentment, with the ensuing conflict reduced to wounded pride. In similar fashion, the film is framed as basic workplace stress: a nurse overwhelmed by a difficult patient.

Familial melodrama offers another reduction. Alma and Elisabet are imagined as long-lost sisters, their resemblance and intimacy retroactively explained by concealed kinship. The haunting quality of the cottage is occasionally literalized, with supernatural influence invoked to account for behavioral shifts. Even the medical context is simplified: the psychiatrist’s decision to send them to the seaside is deemed incompetence, an inappropriate treatment plan rather than a structural device.

Some readings propose that Elisabet’s silence is nothing more than fatigue. She is tired of speaking, tired of performing, and requires rest. Others reduce the film to a single thematic axis, suggesting that it is solely about Elisabet’s failure to love her son, with all other elements functioning as distraction. At the most dismissive extreme lies the claim that Bergman simply wished to be obscure, crafting confusion as an aesthetic posture devoid of deeper significance.

These reductive interpretations share a common impulse: to domesticate the film’s complexity. By isolating a singular cause, they transform structural ambiguity into manageable plot logic. Yet their persistence also testifies to the discomfort provoked by unresolved multiplicity. Simplification here functions less as critical negligence than as a coping mechanism in the face of a text that resists containment.

Beyond thematic and allegorical readings, Persona has been approached as an impressionistic work of art, privileging sensory experience over narrative coherence. In this framework, the film functions less as a puzzle demanding resolution than as an arrangement of perceptual intensities. Like impressionist painting, it emphasizes light, atmosphere, and fleeting states of perception rather than stable forms.

Sven Nykvist’s cinematography is central to this understanding. The stark coastal light of the Swedish shoreline produces sharply defined contrasts across the actresses’ faces. Extreme close-ups render skin texture, pores, and minute muscular shifts with almost tactile immediacy. These visual decisions parallel the impressionist commitment to capturing transient light conditions. The environment, including the sea and rocky terrain of Fårö, operates not merely as backdrop but as psychological weather. Calm waters and harsh daylight coexist with moments of shadow and interior dimness, externalizing fluctuating emotional states.

The film’s editing patterns further reinforce this impressionistic structure. The prologue’s discontinuous montage resembles visible brushstrokes, foregrounding construction rather than seamless illusion. Fragmented images accumulate into an emotional field rather than a linear narrative argument. Scenes recur with variation: the monologue concerning Elisabet’s son is presented twice, each iteration shifting focal emphasis, much as a painter might revisit the same subject under altered light.

Subjective perception governs the film’s reality. Events are filtered through unstable points of view, leaving the ontological status of certain sequences indeterminate. The merging of faces dissolves boundaries between individuals, just as impressionist canvases blur contours through modulations of light. Identity becomes fluid, provisional, responsive to perceptual context.

Water imagery underscores this dynamic. The sea functions as reflective surface and distorting medium, suggesting the instability of self-recognition. Repetition operates as aesthetic method: images, gestures, and confessions recur, yet never identically. Each return modifies the previous impression, accumulating into a holistic but non-linear structure.

The film thus privileges mood over declarative meaning. Rather than articulating a thesis, it generates an atmosphere of intimacy, shame, desire, and estrangement. Modernist fragmentation aligns with this approach, presenting experience as discontinuous yet emotionally coherent. The spectator plays an active role, synthesizing fragments into provisional unity. Meaning emerges through perception, not exposition.

Under this interpretation, ambiguity is not a deficit but a deliberate aesthetic principle. The work invites participation, requiring viewers to complete the image in their own act of seeing.

Among the interpretive intensities surrounding Persona, few moments have generated as sustained analytical attention as the discovery of Elisabet’s letter. Within a psychoanalytic framework, this episode functions as a structural catastrophe, precipitating the transformation of the relational field between Alma and Elisabet.

Prior to the letter’s revelation, the dynamic between nurse and patient may be understood in terms of idealization. Alma speaks, confesses, and expands within the space created by Elisabet’s silence. That silence appears receptive, perhaps benevolent. In psychoanalytic terms, Elisabet becomes the locus of the ideal ego, the position from which Alma imagines herself seen, validated, and coherently reflected. The monologic quality of Alma’s speech aligns with analytic transference: the analysand speaks more and more, sustained by the presumed neutrality of the listening Other.

The unsealed letter disrupts this configuration. Written by Elisabet to a third party, it describes Alma’s disclosures in observational, even detached language. The confessions that appeared intimate are reframed as material. The listener is revealed as analyst rather than confidante. This discovery converts idealizing gaze into persecutory gaze. The image in which Alma had invested herself fractures; the specular confirmation collapses.

The scene’s force may be analogized to a hypothetical scenario within psychoanalysis itself: the patient who gains access to the clinical notes of the psychotherapist. The private analytic space is exposed as text, as description, as categorization. The gaze that constituted subjectivity becomes objectifying. Such a reversal destabilizes identity at its foundation.

Subsequent events intensify this rupture. Alma’s emotional oscillation between tenderness and aggression manifests physically in the broken glass incident. The power relation between caregiver and patient becomes unstable, alternating between dependence and domination. The possibility of vampirism, articulated in serious critical discourse, emerges here as structural metaphor: Elisabet absorbs Alma’s speech while returning no reflective confirmation.

The merging faces sequence extends this psychoanalytic logic. Without stable reflection, identity boundaries blur. Alma’s declaration that she is not Elisabet, followed by gestures of identification, underscores the crisis of self-differentiation. When Alma assumes Elisabet’s role before the visiting husband, the interchangeability of identities becomes performative fact.

The catastrophe initiated by the letter thus exposes the fragility of recognition as the basis of subjectivity. The relational mirror no longer stabilizes but threatens absorption. The gaze ceases to confirm and begins to disintegrate.

Beyond character psychology and relational dynamics, Persona situates itself within a broader modernist interrogation of cinematic form. The film’s overt self-reflexivity, announced in the prologue and reiterated in the closing exposure of camera and crew, foregrounds the medium as constructed artifact. The burning celluloid functions not merely as visual shock but as theoretical gesture: representation is unstable, material, and interruptible.

The opening montage assembles heterogeneous images that resist immediate narrative integration: silent comedy fragments, religious iconography implied in the nailed hand, animal slaughter, erotic imagery, and the child reaching toward a projected face. These elements disrupt classical continuity and align the film with European modernist experimentation of the 1960s. Rather than guiding spectators seamlessly into diegetic immersion, the film insists upon mediation.

This reflexivity extends to the central conceit of performance. Elisabet is an actress who ceases to perform verbally, yet remains framed and lit with theatrical precision. Her silence does not negate performativity; instead, it transforms it. The camera’s extreme close-ups convert facial micro-movements into expressive events. In this sense, the insufficiency of spoken language is counterbalanced by the hyper-articulation of the cinematic image. Bergman’s own reflections on the emptiness of words and the limitations of art resonate here: the film both critiques and exemplifies artistic mediation.

Modernist fragmentation is evident in the repetition and variation of key sequences. The doubled monologue concerning Elisabet’s son disrupts temporal linearity and introduces perspectival instability. Reality and dream, memory and projection, become indistinguishable. The spectator is denied a stable epistemological position from which to adjudicate what is “really” occurring. Such indeterminacy situates the film within a lineage that privileges subjectivity over objectivity.

Political readings intersect with this formal experimentation. The insertion of news footage depicting self-immolation has been linked to Cold War anxieties and the global crisis of meaning in the nuclear age. Even if Bergman declined to specify political intention, the image situates private psychological drama within a broader historical horizon of violence and despair.

The title itself invites reflection on theatrical lineage. Although Bergman did not explicitly invoke Jungian theory, the Latin origin of “persona” as mask inevitably evokes questions of social role and public façade. Cinema here becomes a site where masks are both worn and stripped away, yet never entirely abandoned.

In exposing its own mechanisms, Persona destabilizes the boundary between representation and reality. The spectator becomes aware not only of characters performing but of cinema performing itself. Modernist self-consciousness thus converges with thematic inquiry into authenticity, further complicating any attempt at interpretive closure.

The critical and cultural reception of Persona forms an essential component of its interpretive history. Upon its release in 1966, the film elicited polarized responses. Some critics regarded its fragmentation and self-reflexivity as excessive formalism, perceiving opacity where others discerned innovation. Conversely, a number of reviewers immediately identified it as a groundbreaking intervention in cinematic language. Over time, consensus has shifted decisively toward the latter position. The film is now widely considered one of Bergman’s masterpieces and a landmark of twentieth-century art cinema.

This evolution in reception underscores the film’s capacity to generate sustained engagement. Its initial incomprehensibility to some audiences has become integral to its canonical status. The very features once deemed alienating, the discontinuous montage, the doubled scenes, the merging faces, the exposure of apparatus, are now cited as evidence of formal daring. The iconic composite image of Alma and Elisabet’s fused faces has entered the visual lexicon of modern cinema, emblematic of identity’s instability.

The film’s influence extends beyond Bergman’s own oeuvre. Subsequent directors have drawn upon its exploration of doubling, female subjectivity, and meta-cinematic reflexivity. Its stark black-and-white aesthetic, anchored in Nykvist’s severe lighting and extreme close-ups, has become a reference point in discussions of psychological minimalism. The island of Fårö, initially a practical shooting location, acquired mythic status through its repeated cinematic deployment.

Interpretively, Persona has demonstrated an unusual capacity to sustain contradictory frameworks without resolution. Psychological, feminist, existential, political, and theological readings coexist alongside meta-cinematic analyses. Even speculative and reductive interpretations, whether extravagant or simplistic, testify to the film’s generative ambiguity. The work’s openness does not signal incoherence; rather, it functions as an engine for critical production.

This proliferation of meaning aligns with Bergman’s own refusal to authorize a definitive explanation. By declining to circumscribe the film’s significance, he effectively institutionalized interpretive plurality. The film’s endurance within academic discourse is thus inseparable from its semantic indeterminacy.

Moreover, the cultural afterlife of Persona reflects broader shifts in spectatorship. Modern audiences, accustomed to fragmented narratives and self-conscious media, may find in the film a prescient articulation of contemporary anxieties regarding identity, performance, and authenticity. Its interrogation of the mask, of silence, and of the gaze resonates within an era saturated by mediated self-presentation.

In tracing reception and legacy, one observes not a stabilization of meaning but an ongoing expansion. Persona persists not because it resolves its tensions, but because it institutionalizes them. Its place within the canon is secured precisely through its resistance to closure, ensuring its continued reanimation within successive interpretive communities.

In approaching a concluding perspective on Persona, it is instructive to return to the structural and perceptual principles that have animated its interpretive history. If previous sections have surveyed production context, authorial commentary, canonical frameworks, speculative exaggerations, reductive simplifications, psychoanalytic ruptures, and modernist reflexivity, what remains is not resolution but recalibration.

One possible synthesis emerges from the impressionistic paradigm outlined earlier. Rather than treating the film as a hermeneutic problem demanding definitive decoding, this approach regards it as an orchestration of perceptual states. Light, texture, silence, and repetition function as primary organizing elements. The narrative does not advance toward revelation; it accumulates intensities.

The etymology of the title reinforces this orientation. The Latin persona designates the theatrical mask through which the actor’s voice sounded. The mask was not merely concealment but amplification, a device enabling projection. In Bergman’s film, the paradox of the mask is central: Elisabet renounces speech, yet remains framed as spectacle; Alma speaks incessantly, yet finds her identity destabilized. Silence and speech alike become modes of performance.

The merging of faces, often treated as metaphysical assertion, may be understood instead as perceptual event. Two surfaces align; light redistributes; contours blur. Identity is rendered as effect rather than essence. Similarly, the repetition of the monologue concerning the son does not resolve the question of maternal guilt but intensifies it through variation. Each iteration alters emphasis, much as shifting light alters color in impressionist painting.

Water, recurrent in the coastal setting, offers a final metaphor. As reflective surface, it produces images that are both accurate and distorted. The self in Persona resembles such a reflection: dependent upon angle, light, and proximity. The film does not posit a stable interior core to be uncovered; it stages the oscillation between surface and depth.

The spectator’s role becomes decisive. Because the film withholds explanatory closure, viewers must synthesize fragments into provisional unity. Meaning is not transmitted but constructed in the act of perception. This participatory demand accounts for the work’s enduring vitality within critical discourse.

If one were compelled to articulate a succinct formulation, it might be this: Persona investigates the tension between being and seeming without dissolving the distinction. The terror lies in exposure; the longing lies in recognition. And perhaps the most unsettling possibility the film intimates is that there is no stable self beneath the mask, only performances assembled from memory and fear.

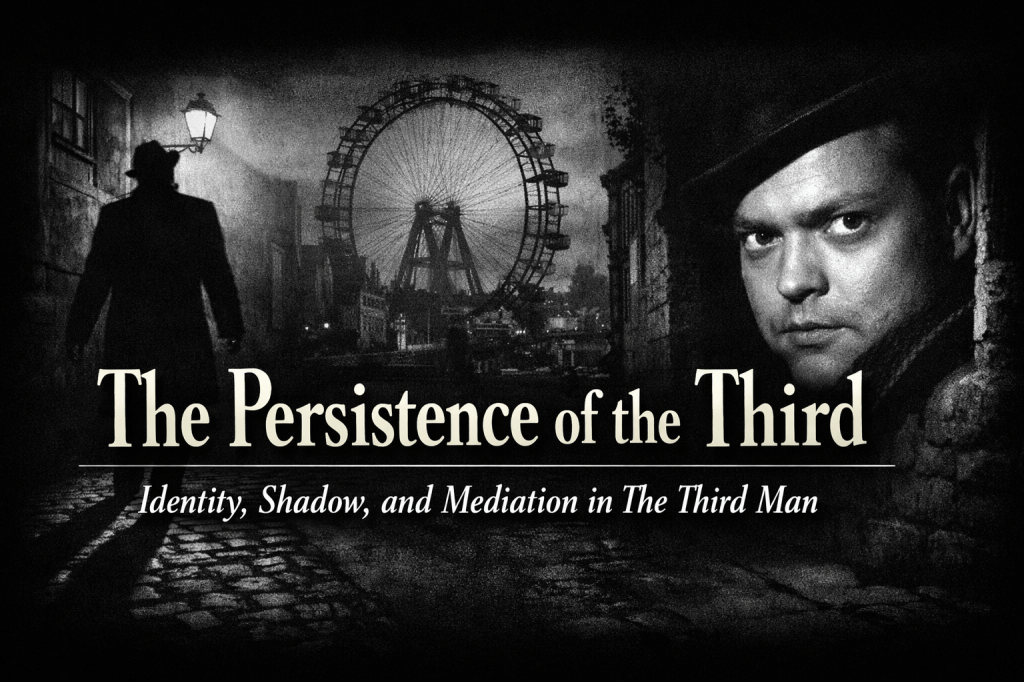

Identity, Shadow, and Mediation in The Third Man

Few films achieve the rare condition in which narrative intrigue, stylistic innovation, historical specificity, and philosophical inquiry converge without diminishing one another. The Third Man is one such work. Released in 1949, directed by Carol Reed and written by Graham Greene, it has long occupied a privileged position in the canon of British and international cinema. Yet its endurance cannot be explained by awards, critical acclaim, or institutional endorsement alone. It persists because it articulates, with unusual precision, a structure of modern moral life.

Set in a Vienna still divided among four Allied powers, the film stages a deceptively simple mystery. An American novelist arrives to find his friend dead. Witnesses contradict one another. A third man is said to have been present. The dead man proves to be alive. A criminal enterprise involving diluted penicillin emerges. A chase unfolds beneath the city’s surface. A second funeral closes the circle.

But this synopsis, while accurate, obscures the film’s governing principle. The central problem is not merely who the third man is, but what the third position represents. At every level—narrative, spatial, ethical, political, and ontological—the film introduces a mediating term that destabilizes binaries. Friend becomes criminal. Authority becomes ambiguous. Loyalty conflicts with justice. East and West fracture into overlapping jurisdictions. Surface civility conceals subterranean commerce.

The film’s formal decisions intensify this triangulated logic. Tilted frames refuse equilibrium. A zither score, at once playful and ironic, unsettles tonal expectation. Key events are withheld from view. Characters are defined as much by what remains unseen as by what is shown. Even the title, with its insistence on definiteness, foregrounds absence before presence.

This essay proceeds from the premise that The Third Man is best understood not simply as a noir thriller or postwar allegory, but as a work structured by what may be called the geometry of the unseen. It will examine the historical conditions of its production; the narrative architecture of withholding; the epistemological function of its visual and sonic design; the paradoxical charisma of Harry Lime; the film’s ethical and political interpretations; the breadth of its interpretive elasticity; its canon formation and contemporary resistance; and finally, the ontological implications of its title.

To analyze the film, then, is to trace the operations of the third term: the concealed intermediary who stands between oppositions and reveals the instability of every apparent pair. In doing so, The Third Man offers not moral instruction, but structural insight. It does not resolve ambiguity. It organizes it.

When The Third Man was released in 1949, it emerged not merely as a thriller but as an artifact inseparable from its historical moment. Directed by Carol Reed and written by Graham Greene, the film was shot in postwar Vienna while the city remained divided into four occupation zones administered by the Allied powers. This geopolitical fragmentation is not incidental backdrop but structural condition. The film’s atmosphere of moral instability corresponds precisely to the jurisdictional instability of its setting.

Reed’s decision to shoot extensively on location in bomb-damaged streets was crucial. He later described the Viennese ruins as essential to capturing what he called a “slightly feverish atmosphere.” Much of the location shooting was undertaken without proper permits from the occupying authorities, underscoring the very administrative fissures the narrative dramatizes. The sewer system, which Reed called “a gift to a filmmaker,” required three weeks of filming across real tunnels and studio recreations. Its realism is not aesthetic flourish; it is infrastructural fact.

The production history is equally shaped by contingency. Anton Karas, an unknown Viennese zither player, was discovered by Reed in a wine garden during scouting. Brought to London for seven weeks, Karas composed and performed a score entirely on the zither—an instrument previously absent from mainstream film scoring. The result was the now-famous “Harry Lime Theme,” which became an international hit, selling over half a million copies and later adapted for the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime, in which Orson Welles reprised his role. The music’s popularity was not foreseen; it was, in Reed’s words, a fortunate accident.

Welles himself, cast as Harry Lime, appears on screen for roughly eight minutes. Reed initially worried about Welles’ reputation for creative interference and deliberately limited his presence on set until necessary. Yet Welles contributed materially, improvising the celebrated “cuckoo clock” speech during the Ferris wheel scene and adding gestures—most famously the fingers reaching through a sewer grate—that became iconic. The collaboration between Reed and Greene was, by contrast, unusually harmonious, with Greene publishing a novella version to clarify narrative logic before scripting.

Institutionally, the film was immediately recognized: it won the Grand Prix at Cannes and the Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Cinematography. In 1999 it was voted the greatest British film of all time by the British Film Institute. Yet its American release was shortened by eleven minutes under producer David O. Selznick, who also pressed for a happier ending. Reed resisted, insisting on the final unbroken shot of Anna walking past Holly to avoid sentimentality.

What Reed did not claim is equally instructive. He never suggested the film was tourism propaganda, nor that Dutch angles resulted from damaged equipment. The Ferris wheel scene was shot on a functioning wheel, not miniatures. The zither score was not a compromise after a studio fire. There was no disastrous falling-out with Greene, no hidden autobiographical motive behind Anna’s rejection, no intended noir trilogy with Odd Man Out, no twin-brother twist in an earlier draft. These apocryphal attributions illuminate how quickly myth accrues around canonical works.

Thus, from its inception, The Third Man was shaped by a convergence of historical fracture, artistic control, improvisational contingency, and later institutional consecration. Its divided city was real. Its atmosphere was deliberate. Its mythology, however, requires careful separation from documented fact.

At the level of plot, The Third Man presents itself as a classical investigation narrative. Holly Martins, an American writer of pulp Westerns, arrives in Vienna to accept employment from his childhood friend Harry Lime. Instead he is greeted with news of Lime’s death in a traffic accident. At the funeral he meets Major Calloway of the British Military Police and Sergeant Paine, the latter an admirer of Martins’ novels. Calloway advises him to leave Vienna immediately. Martins refuses.

The refusal initiates the film’s central enigma. Witnesses claim that two men carried Lime’s body from the street; a porter insists there was a third. This “third man” becomes the axis of narrative obsession. The structure is deceptively simple: arrival, funeral, inquiry, contradiction, revelation. Yet within this scaffold lies a sophisticated architecture of withholding.

Crucially, the film denies the spectator access to foundational events. We never see the planning of Lime’s staged death. We do not witness the inception of the penicillin racket, nor the recruitment of Kurtz and Popescu. The childhood friendship between Martins and Lime is invoked but never dramatized. Anna’s relationship with Lime, including how he secured her forged papers to protect her from Soviet repatriation, remains off-screen. Even the week between Lime’s supposed death and Martins’ arrival is elided. The film thus aligns audience knowledge with Martins’ partial ignorance. Mystery arises not from complication but from strategic absence.

The supporting characters function as moral coordinates within this withholding structure. Martins is not the titular “third man,” yet he is the narrative’s moral trajectory: naïve, loyal, resistant to unpleasant truth. Calloway initially appears antagonistic, but gradually emerges as a pragmatic agent of justice, representing the uneasy authority of occupation forces attempting cross-national cooperation. Anna Schmidt, unwaveringly devoted to Lime even after learning of his crimes, embodies the tension between personal loyalty and moral accountability.

Peripheral figures intensify instability. The “Baron” Kurtz, Dr. Winkel, and Popescu each perform civility while concealing complicity. Popescu eventually attempts to have Martins killed, transforming suspicion into violence. Karl, the waiter at the Casanova Club, provides crucial information before being murdered. The porter who insists on the third man is likewise silenced. Koch, a nervous neighbor, becomes increasingly unsettled as Martins probes further. Hansl, a child who identifies Martins as a “murderer,” catalyzes confrontation with Anna. Crabbin, the cultural attaché who mistakenly celebrates Martins as a literary luminary, offers comic misrecognition that underscores Martins’ displacement. The hospital administrator who shows Martins children harmed by diluted penicillin becomes the narrative’s ethical fulcrum.

The revelation scene—Lime illuminated in a doorway, alive—restructures everything retrospectively. The mystery of the third man collapses into recognition: Lime himself was the missing figure at his own accident. The film then pivots from investigation to moral reckoning. Calloway discloses the full scope of the racket: stolen penicillin diluted and sold on the black market, causing deaths and permanent disabilities, especially among children. Martins’ disbelief yields to horror.

The climactic pursuit through Vienna’s sewers literalizes descent into hidden infrastructure. Wounded and cornered, Lime is ultimately shot by Martins at Lime’s own silent request. The narrative closes with a second funeral, mirroring the first. In the final unbroken shot, Anna walks past Martins without acknowledgment, rejecting romantic resolution.

Thus the film’s narrative architecture depends less on twists than on asymmetry: what is unseen outweighs what is shown; what is withheld generates ethical pressure; and what appears to be a murder mystery reveals itself as a study in loyalty, betrayal, and the cost of knowledge.

If the narrative of The Third Man is constructed through withholding, its style makes that epistemological instability visible and audible. The film’s most immediately recognizable feature—its persistent use of tilted or “Dutch” angles—was not an accident of damaged equipment, as later myths have suggested, but a deliberate strategy. Carol Reed explained that these compositions were designed to evoke the “strange, slightly feverish atmosphere” of postwar Vienna. The tilted frame is not decorative distortion; it is a visual analogue for moral disequilibrium. Vertical lines refuse to remain vertical. Architecture appears unreliable. The city itself seems to lean.

This visual instability is intensified by shadow. Shot in black-and-white, the film deploys high-contrast lighting that renders doorways, staircases, and rubble as zones of ambiguity. The celebrated doorway reveal of Harry Lime depends entirely on chiaroscuro: darkness holds him; light releases him. The visual world withholds as insistently as the narrative.

Sound performs a parallel function. The decision to score the entire film with a solo zither was unprecedented. Discovered by Reed in a Viennese wine garden, Anton Karas was brought to London to record a soundtrack that rejected orchestral conventions. The result is a score at once local and estranging. The “Harry Lime Theme” operates as a leitmotif, recurring whenever Lime is mentioned or present, sometimes brisk and playful, sometimes slowed or distorted.

The music’s tonal brightness creates an ironic counterpoint to the narrative’s darkness. Rather than underscoring tragedy with solemn orchestration, the zither suggests mischief, lightness, even charm. When Lime appears in the doorway, the theme plays fully, marking his presence before moral judgment can intervene. During the Ferris wheel scene, variations of the theme accompany his detachment, its familiarity now unsettling. In the sewer chase, the music becomes more urgent and staccato, building tension without abandoning its melodic identity. At the second funeral, the melody persists in somber variation, refusing catharsis while maintaining structural continuity.

The opening of the film establishes this sonic world immediately: the zither accompanies images of Vienna’s ruins, binding place and sound into a unified atmosphere. This singular instrumentation also helped popularize the zither internationally, transforming Karas from unknown musician into unexpected celebrity. That the theme later anchored the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime confirms its role as both narrative device and cultural export.

Spatial metaphors further consolidate style as meaning. The Ferris wheel in the Prater introduces verticality as moral perspective. From its height, Lime reduces human beings to “dots,” literalizing abstraction. Physical elevation becomes ethical detachment. By contrast, the sewers represent descent into hidden infrastructure—the underbelly beneath reconstructed façades. They are both geographical reality and metaphorical unconscious, a circulation system of corruption flowing beneath civilization’s surface.

Even the film’s pacing participates in this epistemology. Long dialogue scenes, extended takes, and the refusal of rapid montage compel attentiveness. The final unbroken shot of Anna walking past Holly denies the viewer the relief of editing. Style here is not ornament but demand.

Thus, image and sound in The Third Man do not illustrate the narrative; they constitute its argument. The tilted frame, the plucked string, the vertical ascent and subterranean descent all converge on a single proposition: perception itself is unstable, and moral clarity cannot be achieved from a level horizon.

If style destabilizes perception, Harry Lime destabilizes moral judgment. Portrayed by Orson Welles, Lime appears on screen for approximately eight minutes, yet his gravitational pull shapes the entire film. He is, paradoxically, both absent and omnipresent. For nearly half the narrative he exists only as rumor, corpse, memory, and discrepancy. The mystery of the “third man” is in fact the mystery of Lime’s deferred embodiment.

His first physical appearance—standing in a doorway illuminated by a sudden shaft of light—has become one of cinema’s most iconic reveals. The scene depends on timing, shadow, and the unexpected intervention of a stray cat that recognizes its master before any human character does. Lime’s smile, relaxed and amused, disorients both protagonist and spectator. Resurrection replaces death; certainty dissolves into complicity.

Lime’s criminal enterprise is by now clear: he has stolen penicillin from military hospitals, diluted it, and sold it on the black market, causing countless deaths and permanent injuries, particularly among children. Yet he never expresses remorse. His charm is not incidental to his villainy; it is its enabling condition. He speaks with wit, warmth, and cosmopolitan detachment. He invokes shared childhood memories with Holly Martins, leveraging nostalgia as persuasion. He provides Anna with forged papers to protect her from Soviet authorities, yet simultaneously exploits her loyalty as cover.

The Ferris wheel scene crystallizes this moral abstraction. From above, Lime gestures toward the people below as “dots,” asking whether one would truly refuse money if some of those dots ceased moving. Here distance becomes doctrine. Human beings are reduced to units of exchange. In the same conversation he delivers the improvised “cuckoo clock” speech, contrasting Renaissance Italy’s violence with Switzerland’s peaceful production of a trivial object. The historical claim is dubious; its rhetorical function is devastating. Lime reframes atrocity as generative energy.

This detachment extends into performance history. Welles reportedly demanded changes to the script and contributed improvised moments, including the sewer-grate gesture—fingers reaching upward through iron bars—that became another indelible image. After the film’s release, the character proved so popular that Welles reprised Lime in the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime, extending the character’s mythology beyond the film’s temporal boundaries.

Lime’s death in the sewers restores narrative symmetry: the first funeral false, the second authentic. Wounded and cornered, he silently requests that Holly end his suffering. Martins complies, completing the tragic arc of childhood friendship turned lethal. Yet even in death, Lime’s charisma lingers. He remains one of cinema’s most compelling villains precisely because he attracts as he repels. The audience experiences moral tension not despite his appeal but because of it.

In Lime, the film articulates a theory of modern villainy: evil not as grotesque excess, but as urbane calculation; not as hysteria, but as charm; not as rage, but as distance. Screen time proves irrelevant to impact. Presence becomes a function of memory, rumor, and performance. Lime is the third man not simply because he stood at his own staged accident, but because he occupies the third position between morality and monstrosity: the position of seduction.

Beyond its narrative precision and stylistic audacity, The Third Man endures because it stages a profound ethical inquiry. The film is frequently interpreted as a meditation on postwar moral ambiguity: in a world devastated by conflict, traditional binaries of good and evil no longer function with reassuring clarity. Vienna, carved into sectors governed by competing powers, becomes a microcosm of the emerging Cold War. Political fragmentation mirrors moral fracture.

One influential reading understands Holly Martins as a critique of American naïveté. He arrives in Europe armed with the moral simplifications of his Western novels, expecting loyalty to align neatly with virtue. Instead, he confronts a city in which survival has required compromise. His eventual decision to assist Major Calloway in trapping Lime signals a painful maturation, but not triumph. He acts without transcendent assurance; he chooses rather than inherits moral certainty.

Lime, by contrast, has been read as an embodiment of unrestrained capitalism. His penicillin racket commodifies human life with chilling efficiency. In weighing the profit from diluted medicine against the anonymous suffering of children, he articulates a market logic stripped of ethical constraint. Economic desperation, the film suggests, does not create corruption ex nihilo, but amplifies latent opportunism. The black market emerges less as aberration than as shadow economy.

The film also interrogates the tension between loyalty and justice. Anna’s unwavering devotion to Lime, even after learning of his crimes, challenges liberal assumptions about moral accountability. Her final walk past Holly refuses sentimental reconciliation and can be interpreted as a rejection of American romantic optimism in favor of a more tragic European understanding of fidelity. Calloway, meanwhile, represents an internationalist pragmatism that transcends narrow patriotism. His pursuit of Lime is not nationalist vengeance but institutional responsibility across borders.

Existentialist interpretations further complicate the ethical landscape. In a world devoid of clear metaphysical guidance, characters must act without guarantees. Holly’s final shot of Lime is not sanctioned by higher authority; it is an act of chosen responsibility in an absurd environment. The sewers thus become not only physical underworld but metaphorical descent into moral choice.

Other serious readings emphasize betrayal as structural principle: Lime’s betrayal of humanity through his crimes; Holly’s betrayal of friendship; Anna’s perception of betrayal by Holly. Still others focus on dehumanization through perspective, the Ferris wheel height symbolizing privilege’s capacity to abstract suffering.

The film’s key thematic propositions may be distilled as follows: charisma can mask monstrosity; naïveté can enable complicity; appearances deceive; distance enables cruelty; systems create shadows; individual choices reverberate widely; and complexity, rather than moral instruction, engenders longevity.

In this sense, The Third Man neither offers a moral lesson nor abdicates moral inquiry. It situates ethics within historical contingency, refusing both absolutism and nihilism. The divided city becomes a laboratory in which friendship, profit, loyalty, and justice are tested under conditions of scarcity and political fragmentation. The result is not clarity, but lucidity.

If The Third Man sustains canonical status, it does so not only because of formal precision or historical resonance, but because it tolerates interpretive expansion without collapse. The film invites projection. It can be overread, underread, allegorized, psychologized, moralized, or flattened—and yet it remains structurally intact. This elasticity is itself evidence of design.

At one pole lie outlandish readings that transform the narrative into metaphysical speculation. Some interpret the entire film as Harry Lime’s near-death experience, with Vienna functioning as purgatory in which he confronts moral failure before his “true” death in the sewers. Others reverse perspective entirely, suggesting that Holly Martins is dead throughout, wandering a liminal city as a ghost unaware of his own demise. Vienna becomes not historical space but shared hallucination, its tilted angles and surreal lighting explained as symptoms of postwar trauma-induced psychosis.

More ambitious allegories proliferate. The sewers are read as the collective unconscious; Lime as humanity’s repressed shadow self; the Ferris wheel as cosmic vantage point from which human insignificance is revealed. In a more whimsical register, the film has been reframed as a chess match—Vienna as board, Lime as black king, Holly as white knight, Anna as queen constrained by loyalty. Hyperbolic interpretations recast the narrative as proto-digital parable of internet scams, or as an intertextual prequel to Citizen Kane, with Lime surviving to become Charles Foster Kane. The title itself has been linked to the “third man factor,” inverted from protective presence into existential threat.

Such readings, while excessive, are not purely frivolous. They testify to the symbolic density of the film’s design. That it can bear such transpositions suggests that its structural triangulation extends beyond plot mechanics into metaphoric architecture.

At the opposite pole lie reductionist interpretations. Here Lime becomes merely “a greedy jerk.” The film reduces to the moral slogan “crime doesn’t pay.” The sewer chase is seen as little more than a climactic action set-piece. Anna becomes foolish rather than tragic; Holly merely naïve rather than ethically conflicted. The Dutch angles signify simply that “everything is messed up.” The mystery of the third man is flattened into a conventional whodunit device designed to sustain suspense until the midpoint reveal.

These simplifications are understandable. The narrative can, at a superficial level, sustain them. Yet they evacuate the film’s central tension: the triangulation of loyalty, justice, and charisma; the abstraction of human life into economic units; the instability of identity in a fractured political landscape.

The coexistence of excess and reduction reveals something essential. Interpretive elasticity is not accidental. It is generated by deliberate withholding, structural asymmetry, and tonal irony. The film neither forecloses allegory nor enforces doctrine. It resists totalization and simplification alike.

Thus The Third Man occupies a rare interpretive middle ground. It is neither hermetically sealed nor infinitely malleable. It invites theoretical elaboration while retaining narrative coherence. Its third position—between binary poles of overreading and underreading—remains operative even in its reception.

The elevation of The Third Man into the cinematic canon was neither accidental nor immediate mythmaking, but the cumulative result of innovation, institutional endorsement, and interpretive endurance. From its release in 1949, the film was recognized for formal distinction. It won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and secured the Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Cinematography. These honors did not merely reward technical excellence; they signaled that a thriller set amid postwar ruins could achieve artistic prestige.

Over subsequent decades, its reputation consolidated. Critics repeatedly cited its visual daring, narrative economy, and tonal complexity. In 1999, the British Film Institute voted it the greatest British film of all time, an accolade that cemented its position within national and international film history. The film’s influence extended beyond cinema: the “Harry Lime Theme” became globally recognizable, and the character’s afterlife in radio reinforced his cultural presence. Few films achieve such synthesis of art-house credibility and popular appeal.

Several factors explain this canonization. Its cinematography established a visual language that shaped film noir and influenced generations of filmmakers. Its unconventional zither score demonstrated that soundtracks could redefine narrative mood rather than simply accompany it. Welles’ performance proved that minimal screen time need not diminish impact. The sewer chase sequence set new standards for tension and location realism. The final unbroken shot defied Hollywood’s demand for romantic resolution, illustrating the power of visual storytelling over sentimental closure. Above all, the film achieved rare unity: writing, directing, acting, and technical execution converged without visible strain.

Yet canonization generates friction. Contemporary audiences, shaped by rapid editing and heightened spectacle, often find the film’s pacing deliberate to the point of austerity. Extended dialogue scenes and gradual narrative revelation test attention spans accustomed to acceleration. The black-and-white palette, once standard, can appear archaic to viewers habituated to color saturation.

Historical distance compounds this difficulty. The four-power occupation of Vienna, the mechanics of postwar scarcity, and the subtleties of European political realignment are no longer common knowledge. Without contextual awareness, the stakes of black-market penicillin may feel abstract, especially in the absence of graphic depiction. The film’s refusal to provide explicit backstory—about Holly and Harry’s childhood bond, or Harry and Anna’s romance—contrasts sharply with contemporary expectations of psychological exposition.

Formal choices can also unsettle. The Dutch angles may strike modern viewers as exaggerated rather than expressive. The zither score, once radical, can feel tonally dissonant or repetitive. The sewer chase, groundbreaking in its time, lacks the kinetic intensity of contemporary action cinema. The delayed physical appearance of Harry Lime—nearly halfway through the film—creates a narrative asymmetry unfamiliar to audiences expecting early introduction of key figures.

Most unsettling, however, is the film’s moral ambiguity. It offers no uncomplicated hero. Holly is naïve; Calloway is emotionally restrained; Anna remains loyal to a criminal; Lime is charismatic yet monstrous. The ending refuses catharsis. Anna’s silent walk past Holly denies emotional resolution. For viewers accustomed to closure, this restraint can feel anticlimactic.

Thus, the very qualities that secured the film’s canonical status—its stylistic boldness, ethical complexity, and refusal of simplification—also account for contemporary resistance. Canon is not comfort. It is durability under changing conditions of perception. The Third Man endures not because it conforms to modern taste, but because it resists assimilation, compelling each generation to renegotiate its expectations of narrative, morality, and form.

If The Third Man sustains interpretive endurance, it does so most concisely in its title. The phrase appears at first to designate a simple plot device: the unidentified figure present when Harry Lime’s supposed corpse was carried from the street. The porter insists there were three men; official testimony claims only two. This discrepancy drives the investigation and structures narrative suspense. The audience initially assumes that the third man is the murderer. The revelation—that he is in fact the presumed victim, alive and complicit in his own deception—reverses expectation.

Yet the title’s meaning expands beyond its literal referent.

Numerically, Lime is the third member of his own criminal configuration alongside Kurtz and Popescu. The film is structured through triangular relations: Holly–Anna–Harry; Lime–Kurtz–Popescu; the American, British, and Soviet occupation authorities. The geometry of three destabilizes binary oppositions. Instead of simple dualisms—good versus evil, loyalty versus betrayal—the film operates through triangulation. A third term complicates every moral equation.

The definite article intensifies this singularity. It is not a third man, but the third man. The phrase signals uniqueness, even inevitability. This figure is not incidental; he is structurally central. The title, in retrospect, is ironic: the so-called peripheral mystery is in fact the narrative’s gravitational core.

Symbolically, the third man evokes the hidden self beneath public façade. Lime stages his own death and moves invisibly between sectors of the divided city, embodying the instability of identity in a fractured world. The title resonates with philosophical discourse, recalling the so-called “third man argument” concerning how identities are recognized across instances. In a film obsessed with mistaken and concealed identities, such resonance is not accidental but suggestive.

Theological echoes also linger. The triadic structure evokes the Christian Trinity, yet inverted. Instead of Father, Son, and Spirit, we encounter charm, intelligence, and corruption. Salvation is replaced by opportunism. In another interpretive register, the phrase recalls the “third man factor,” a psychological phenomenon in which individuals under extreme stress sense an unseen presence offering guidance. Here the inversion is complete: the third presence in Vienna does not save but endangers.

Even allegorical readings extend from the title. Some interpret the third man as a metaphor for a “third way” emerging in postwar Europe, neither wholly Eastern nor Western but morally ambiguous between ideological poles. Others see in the title a folk-tale cadence—the third brother, the third wish—suggesting mythic pattern beneath realist surface.

Ultimately, the title functions as ontological key. It names absence before presence, rumor before revelation, shadow before embodiment. The third man is the concealed participant in transactions, the beneficiary of systemic gaps, the figure who thrives between jurisdictions. He is also the structural reminder that every apparent binary conceals a mediating term.

In naming him, the film names its own method. It proceeds not through opposition but through triangulation. The third position destabilizes certainty and exposes hidden alignments. Thus the title does not merely identify a character. It articulates the film’s governing principle: the persistence of the unseen intermediary in modern moral life.

If one surveys the full architecture of The Third Man—its production history in a divided Vienna, its carefully engineered narrative asymmetries, its tilted visual field, its singular zither score, its constellation of morally ambivalent figures, its interpretive elasticity, and its canonical endurance—one principle emerges with increasing clarity: the film is organized around absence.

Harry Lime appears only briefly, yet dominates the film’s gravitational field. The unseen planning of his fake death shapes the plot. The unshown victims of diluted penicillin haunt its ethical stakes. The week between his staged accident and Holly’s arrival remains inaccessible. The backstories of friendship and romance are invoked but withheld. Even the political architecture of Vienna is partially occluded, understood through implication rather than exposition.

Absence generates structure.

This logic extends to reception. The film’s elevation into the canon was reinforced by institutions and critics, yet it remains resistant to assimilation. Contemporary viewers often experience friction precisely because the film refuses explanatory surplus. It withholds spectacle, backstory, sentimentality, and moral reassurance. What it offers instead is atmosphere, ambiguity, and implication.

The interpretive field surrounding the film further confirms its structural elasticity. Serious readings locate it within Cold War geopolitics, existential ethics, and critiques of capitalism. Simplistic readings flatten it into moral parable. Outlandish readings inflate it into purgatory allegory or metaphysical dreamscape. The film accommodates these projections without collapsing, suggesting that its core design contains deliberate openness.

At the center of that openness stands the title. The “third man” is at once literal participant, structural mediator, economic opportunist, psychological shadow, and ontological category. He occupies the space between binaries: friend and criminal, loyalty and justice, East and West, life and death. He is the intermediary who thrives in the gap.

In this sense, The Third Man anticipates a modern condition. Postwar Vienna is not merely historical setting but prototype of a world in which authority is fragmented, economies are shadowed, and identities are unstable. The film proposes that moral life unfolds not along clean lines but within triangulated fields where unseen actors shape visible outcomes.

The enduring power of the film lies in its refusal to eliminate the third term. It does not restore equilibrium by collapsing complexity into closure. The final shot—Anna walking past Holly—leaves the triangle unresolved. Friendship, justice, and love do not reconcile.

What remains is the central absence: the recognition that beneath every apparent dualism there may stand a third figure, unacknowledged yet decisive. In naming him, the film names the condition of modernity itself.

In one sense, the periodic table is complete up to a point: all chemical element slots through atomic number 118 have been discovered or synthesized. In 2016 the last missing entries of the seventh period – elements 113, 115, 117, and 118 – were officially confirmed and named (nihonium, moscovium, tennessine, and oganesson), thus filling out the table’s seventh row (cen.acs.org). However, the notion that the elemental chart is permanently complete could not be further from the truth (www.americanscientist.org). The periodic table remains open-ended, with new elements beyond 118 potentially waiting to be created and added as science progresses. In short, while the known chart is full through element 118, it is not considered a finished entity in a long-term sense.

After element 118, a new period would begin – and it remains blank. No element with atomic number 119 or higher has yet been synthesized or confirmed, so officially the table stops at 118 for now. These super-heavy elements (119, 120, and beyond) are hypothesized to exist, and scientists are actively searching for them. In fact, the global race to discover element 119 (and 120) is well underway (cendevredesign.acs.org). The first team to create element 119 would essentially start an eighth row of the periodic table (cendevredesign.acs.org), marking the first addition to the chart since 2016. Laboratories in several countries – notably Japan, the United States, Germany, Russia, and China – have been developing powerful experimental setups to attempt these syntheses (cendevredesign.acs.org) (cendevredesign.acs.org). Among them, Japan’s RIKEN institute has emerged as a frontrunner: it invested in a custom-built particle accelerator upgrade specifically to hunt for element 119 one atom at a time (cendevredesign.acs.org). Meanwhile, U.S. researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) have been pursuing element 120 with their own approach (cendevredesign.acs.org). These concerted efforts show that the table is poised to grow, even though the next elements remain undiscovered so far.

Pushing beyond element 118 is an enormous scientific challenge. All known superheavy elements are extremely unstable, often decaying in a split-second or less (www.scientificamerican.com). The greater the atomic number, the more protons jam-packed into a nucleus – and generally, the more quickly that nucleus falls apart. This means any new element must be created and detected almost instantaneously before it vanishes. Researchers synthesize superheavy atoms by smashing lighter nuclei together at very high speeds, hoping the fragments fuse into a new, heavier nucleus. The probabilities are extremely low: for example, when RIKEN’s team in Japan discovered element 113 (nihonium), they had to perform about four trillion atomic collisions to produce three atoms of nihonium, each of which existed for only a few milliseconds (cendevredesign.acs.org). That was enough to confirm its discovery, but it vividly demonstrates the difficulty of making and observing such fleeting atomic species. Attempting to reach element 119 or 120 is even harder – it requires heavier projectile ions, rarer target materials, and months or years of sustained experiment, all for a handful of decay signals. So far, no experiment has definitively seen element 119, underscoring how demanding this frontier is.

Despite the hurdles, recent advancements give reason for optimism. Cutting-edge facilities and techniques are improving the odds of success. In 2020, RIKEN completed a major upgrade to its heavy-ion accelerator and separator systems, boosting the beam intensity and energy needed to form element 119 (link.springer.com) (link.springer.com). Similarly, scientists in the U.S. have developed a novel method to produce superheavy nuclei more efficiently. In mid-2024, a team at LBNL reported using an intense beam of titanium-50 (a rare isotope) to successfully forge atoms of element 116 (livermorium) in a new way (www.scientificamerican.com). Livermorium had been made before, but this experiment was groundbreaking because it proved a more effective fusion approach that could be applied to reach heavier, yet-unknown elements (www.scientificamerican.com). According to researchers, this technique “paves the way for the synthesis of new, even heavier elements” by overcoming some prior limitations (www.scientificamerican.com). Each incremental innovation – whether stronger accelerators, improved detectors, or creative reaction choices – increases the likelihood that elements 119, 120, and beyond will eventually be created in the laboratory.

What lies beyond the current table? The truth is, nobody knows exactly how far the periodic table can ultimately extend. Theoretical models predict that nuclei might become a bit more stable again in an “island of stability” around certain high atomic numbers (possibly in the 120s), which raises hope that superheavy elements in that region could live long enough to study (www.scientificamerican.com). Even if those longer-lived superheavy atoms exist, reaching them will require pushing technology to its limits. At some point, fundamental physical constraints – such as the immense electrostatic repulsion in ultra-heavy nuclei or relativistic effects on electrons – may impose a practical upper limit on the periodic table. Scientists have speculated about a possible end to the table (some estimates range from around element 126 to somewhere around 150 or beyond), but no one can say for sure where the cutoff lies. What we can say is that as of today the elemental chart is not a closed book. It continues to grow gradually: each time a new element is synthesized and confirmed, another slot gets filled and our understanding of atomic science expands. In summary, the periodic table is complete only up to the elements we have discovered so far – it remains incomplete in a broader sense, with ongoing research poised to add new entries as soon as nature allows (cendevredesign.acs.org).

Further Reading:

Learn more: